On this International Day of Persons with Disabilities – and with the Trump administration promising to dismantle the Department of Education and the possible effects of that on disabled students along with so many in the 92% of Black women voting coterie stepping back to recalibrate how we’re planning to support our own in our own ways – this is the perfect time to talk about how the rest of us Black folks plan to show up for disabled Black folks.

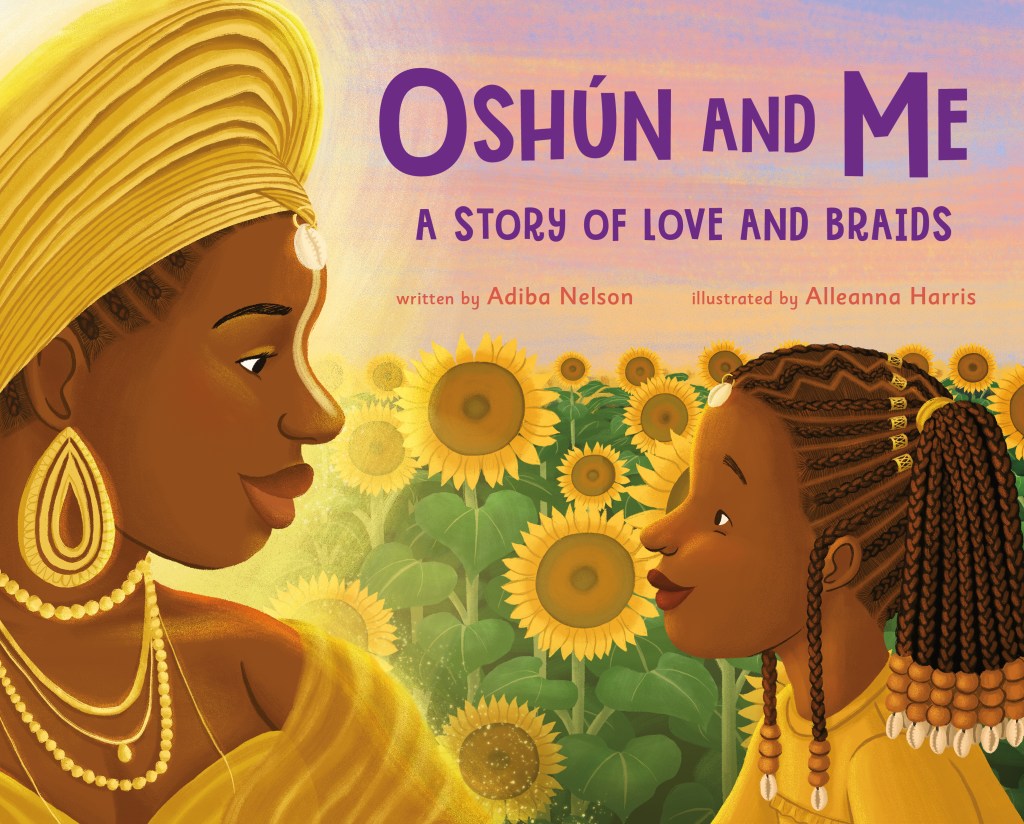

I reached out to author and disability activist Adiba Nelson. When we initially connected back in July, she was debuting the artwork to her latest children’s book, Oshun & Me, a tale about Yadira, a disabled Afro-Latina girl who feels nervous about her first-day-of-school hairstyle, which has a cowrie shell centered on her forehead.

I was hyped about the book and pitched to a Black media outlet – only to be told that their readership didn’t want to read about disability.

That response brought this story to this blog on this day.

What started as a conversation between Nelson and me about Oshun & Me back in the mid-summery, almost – comparatively speaking, halcyon — pre-The Election days turned into a deeper discourse about what Black communities have – and haven’t — done when it comes to disabilities and disabled people in our circles. This was something that Nelson said she wanted to discuss for a long time back then – and it feels more urgent now. The author knows “there’ll be millions of people who’ll disagree with me,” but she said that her ideas about Black communities and disability are what she’s observed and knows about historically.

For example, she told me, what too many Black people don’t realize is that the Civil Rights Movement started out as being about Blackness and disability, However, the Movement leaders realized that it “would go further” in its advocacy efforts for Black people if they dropped the fight for disability rights. Nelson said that she wasn’t sure how or why the decoupling of the rights fight happened — “I don’t know if it’s because the Black equal rights issue was more of a hot-button item at the time – but the end result is the fight for disabled Black folks is rarely, if ever, mentioned when the Civil Rights Movement comes up.

The othering continues today in Black communities, Nelson commented — even with the reality that one in four Black people have a disability and one in six Latine Americans have one. Or the reality that of all the disabled Black people in the U.S., the age group with the highest number is Black people between 55 years old and 64 years old, according to a 2021 CDC report.

One example of this continued othering is the prevalence of Black disabled people in the U.S. unhoused population. A 2023 report from The National Alliance to End Homelessness stated that, as is, 37 percent of Black people experience homelessness. Furthermore, people with mental health disabilities are “vastly overrepresented in the unhoused population,” with one in five dealing with behavioral health issues. Even though Black and White people have the similar rates of mental health issues, Black people have a harder time getting access to treatment, the report stated.

Nelson agreed with this assessment in regards to how the larger Black communities treat Black unhoused people dealing with mental illness, too often “without help, without diagnoses, without anything.”

She also stated that mistrust of the medical and academic professions based on studies and anecdotes passed on generationally when it comes to how they treat Black people in general — let alone those who are Black and disabled — is understandable. The author said that we know our disabled children “are not afforded the same options.” However, that should not stop us as communities to advocate with and for our disabled members, including when the ableism comes from other Black people.

“Disability is the biggest insult we have for each other within our community, and it permeates everything,” the author stated. “It’s in our music; it’s in our TV shows; it’s in the poems that people write. It’s everywhere — and no one questions it. We have these opportunities to really change the way our communities and our cultures speak about and thinks about disability and disabled folks — but we don’t.”

“You could not let Massa know if you had this child that was different because it would be immediate death,” Nelson explained. “So, it became a culture of [our hiding] the differences, [not admitting] the differences. And, in its on little way, it’s carried over to modern-day culture where we see so many young Black boys and girls and Brown boys and girls not getting diagnoses because ‘you’re not going to put that label on my kid; you’re not going to allow my child to be treated differently; I don’t go here with my kid because I don’t want people to look at them.’”

“It was a matter of keeping your child alive,” the author said. “I get it — but we are not there anymore. There are some legal protections that we do have now that says you cannot do that.”

“I just feel like, as a whole, we’ve done a piss-poor job. I know we can do better, and I want us to do better. I don’t know where to start with doing better,” Nelson said. “As a community, we really just need to take the time and really understand what does disability actually mean; what does it mean, and what are we making it. Sometimes — and I’m guilty of this, too — of putting limitations on our kids due to their disability out of protection. But when we do that, we’re allowing the rest of the world to do at.”

That’s why Oshun & Me is such a necessary counternarrative for Black communities, especially during this post-election collective reconsideration.

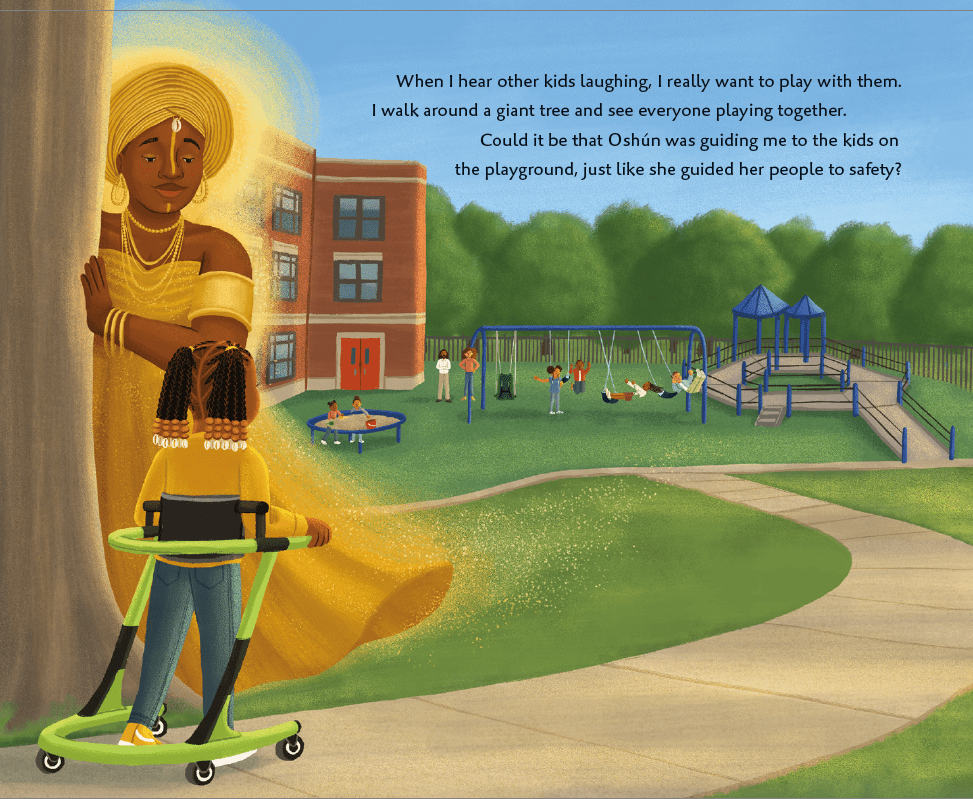

“What I love about [the story] is [Yadira’s] nervousness about being the new kid has nothing to do with her disability,” Nelson said about her latest book, which will drop on January 14, 2025. “It’s, ‘I’m a new kid, and I got this weird shell on my forehead. Why do I have to do this?’ That’s just a regular, degular kid.” Her mom explains the mythic lineage of the cowrie shell, going back to the goddess Oshun.

Boosted by ancestral confidence, Yadira heads to school. When she gets there, “she sees that there are all these kids who are just like her with their braids and their shells,” Nelson said.” I just think it’s a fun, sweet story, and I love that I get to highlight the Afro-Latin culture because I’m Black and Puerto Rican.”

Nelson said her children’s books will always feature a child of color with a visible disability – and that the child’s disability isn’t the focus of the story. Nelson also does her best to advocate for Black illustrators and advises other Black children’s book writers to request to work with Black illustrators, too, because “they aren’t getting enough work out there.”

Oshun & Me’s artist, Alleanna Harris, said the opportunity to work on the book “was a complete joy” and that she learned a lot.

“I wanted to be respectful with the main character, Yadira, whose in a wheelchair. So, I wanted to make sure that was illustrated correctly,” Harris said. “And she also has a gait trainer, so I wanted to make sure that visually, when the [other] kids interact with her, you can tell they weren’t treating her any differently. That it was normal interactions with her mom, the way she gets around — it was [all] normal and that kids and adults can feel that.

Harris said that her being able-bodied meant that it was all the more important for her to get Yadira and the overall tone of the book right.

“I wanted people to identify with [Yadira], Harris stated, “and normalize her being in a wheelchair.”

And that, ultimately, is what Nelson wants out of Black communities – and the larger world. She said her advocacy and art are about to creating a world for her own disabled child and other kids like her.

“It’s my job as [my daughter’s] parent — as a disability rights activist and advocate — to make sure that, at some level, the world is ready to hold my child and other kids like her on a level playing field when I’m not here anymore,” she stated. “So, whatever I need to do to help people see — literally see — disabled people, see the fullness of who they are, see they whole humanity, that’s my job to do that while [I’m] here. I’m hoping that, with whatever stories I write or interviews that I do or articles that I write, I hope that I give that perspective that helps people think about disability in a different way, in a more human way.”

Leave a comment